Here are the key takeaways from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ report, The Employment Situation – October 2024:

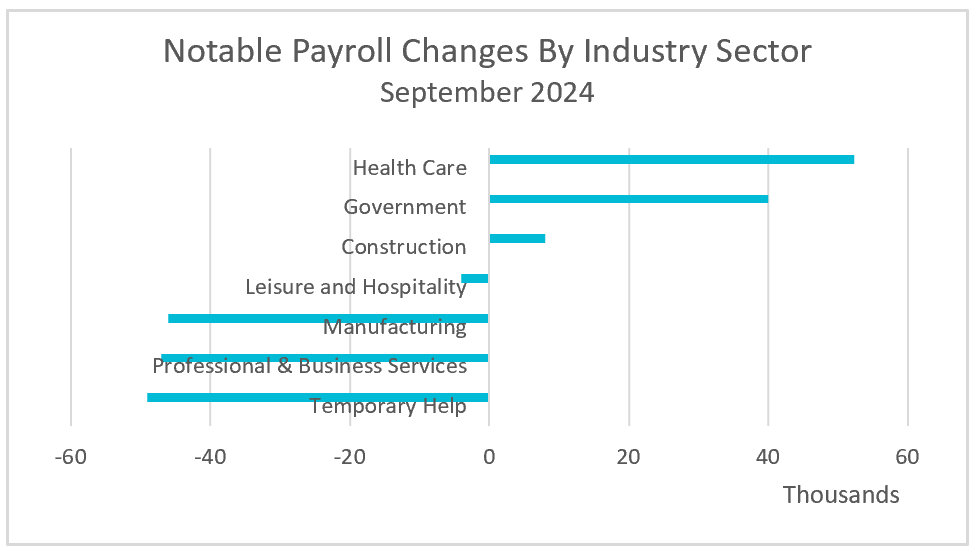

Healthcare and government sectors continued to hire at a robust pace, but storms and strikes significantly slowed hiring in October. Payroll growth plummeted to just 12,000 workers, marking the smallest increase since December 2020, when 306,000 jobs were lost due to a surge in COVID-19 cases and the government’s pandemic response. October’s gain is far below the 12-month average of 194,000. Some of the most notable payroll changes are in the graph below.

Hurricanes Milton and Helene ripped through the Southeast, temporarily taking many workers off payrolls. For example, the leisure and hospitality sector lost 4,000 jobs, compared to an average monthly increase of 24,000 in the third quarter. Boeing’s 33,000 striking workers largely drove the 46,000-job decline in the manufacturing sector. (BLS)

Perhaps most telling are the large downward revisions to payroll figures for August and September. While October’s weak figure can be blamed on storms and strikes, the revisions indicate the labor market is weaker than previously thought.

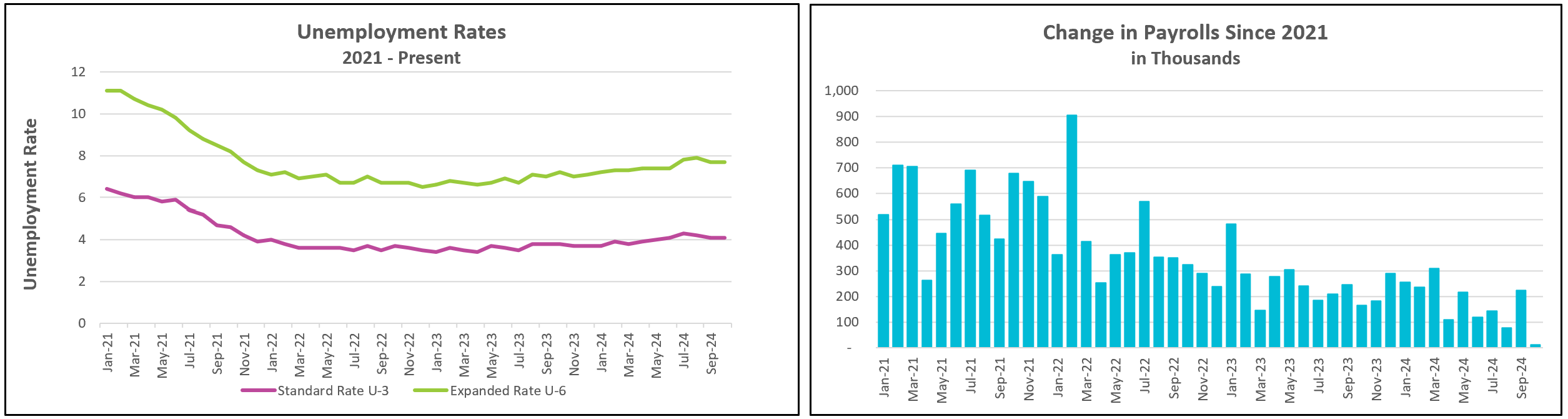

The unemployment rate, however, remained steady at 4.1%, offering more insight into the current employment picture. Workers affected by weather but still employed, and those on strike, are counted as employed. Moreover, the unemployment rate held steady because more people left the labor force. Mathematically, for the unemployment rate to stay at 4.1%, more job losses are required as the labor force shrinks, since the unemployment rate equals the number of unemployed divided by the labor force.

There are other signs of softening in the labor market. Temporary help services declined, which may indicate that companies are expecting weaker demand or tightening budgets. Job openings have decreased by 1.9 million over the past year (JOLTS). Additionally, fewer people are quitting their jobs, suggesting that workers are less confident about finding new employment if they leave their current jobs.

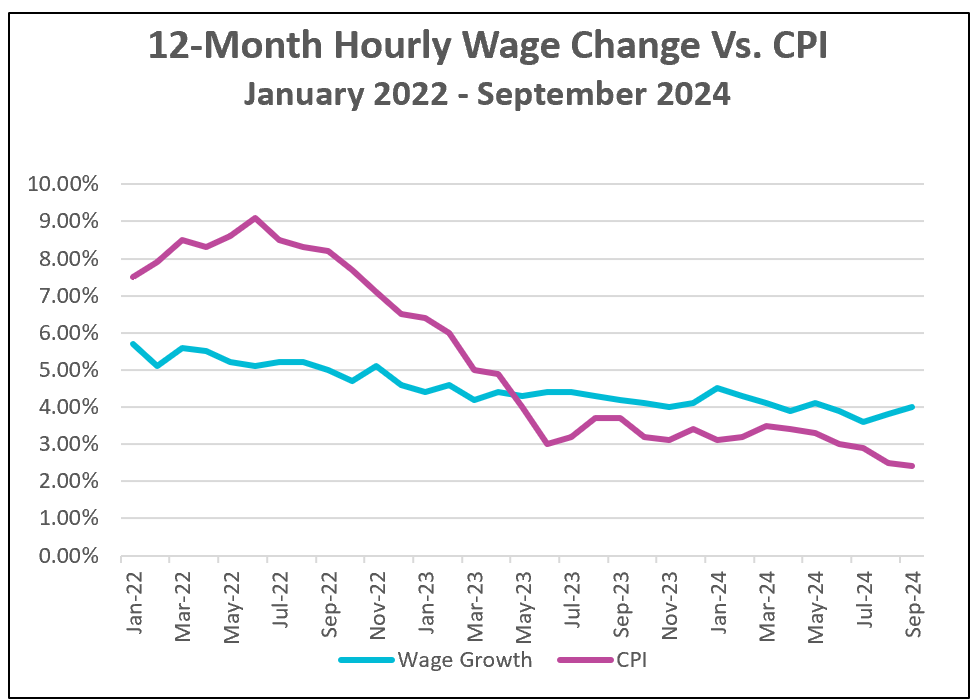

Inflation peaked in June 2020 and challenged many families, especially as food and housing prices surged. Meanwhile, employers struggled with a labor shortage, leading to wage increases. But wage increases did not match price increases because the inflation rate was so high. Policymakers at the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to cool aggregate demand and inflation. The strategy worked, and inflation subsided. Starting in April 2023, monthly wage gains outpaced inflation, helping low-income households better manage their budgets. However, despite higher real wages and a strong labor market, many Americans remain dissatisfied with the economy due to the lingering effects of high prices.

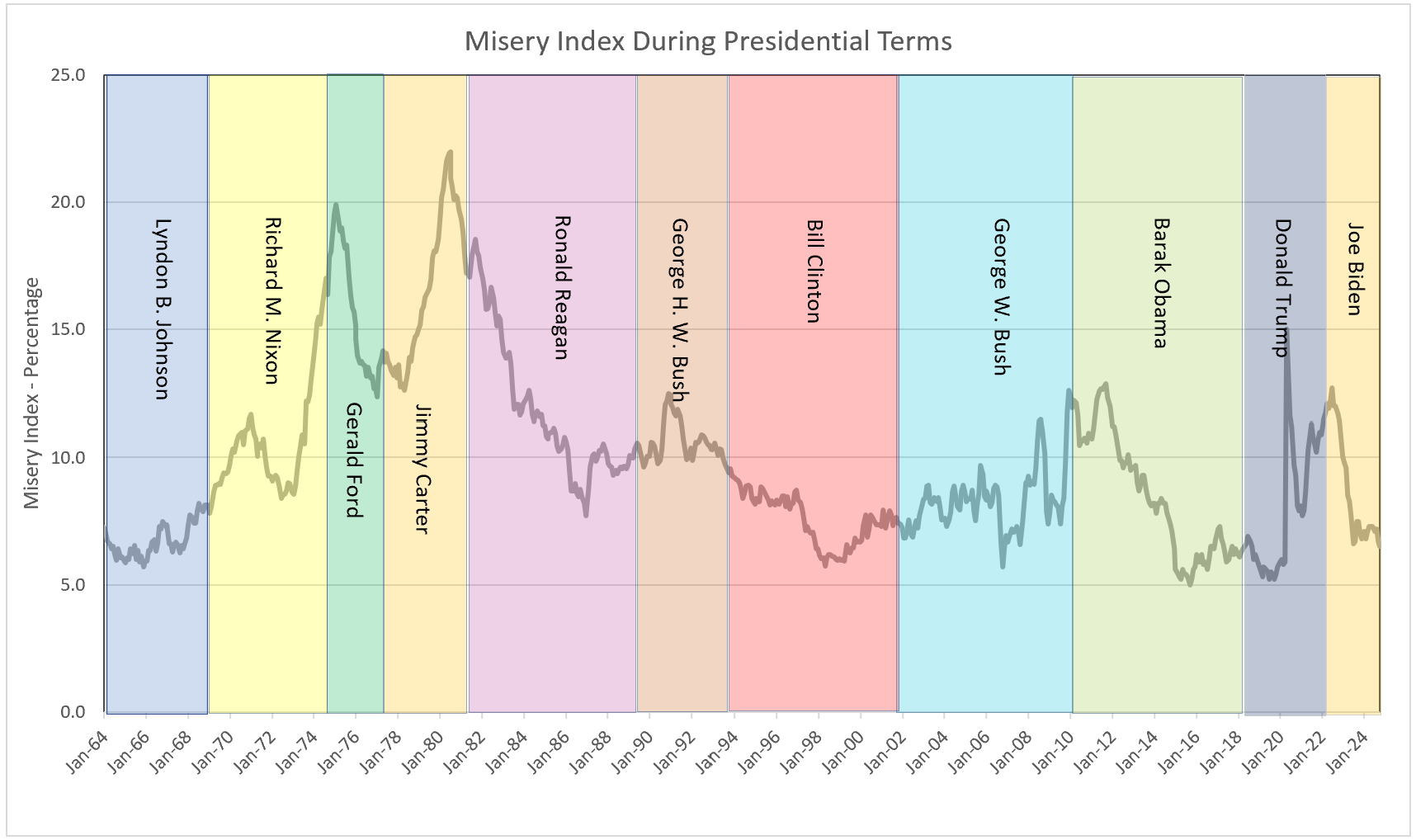

Are Americans truly worse off? Economists track the “misery index” as an indicator of economic distress. It is the sum of the unemployment and inflation rates. During periods of high inflation and unemployment, people often feel a sense of economic hardship. The higher the index, the greater the general “misery" experienced by the population. Under the Biden administration, the misery index has dropped significantly and is at levels not seen since early in the Trump administration. The graph below shows the misery index since the Johnson presidency.

Later this week, Federal Reserve policymakers will meet to discuss monetary policy. The low payroll numbers in this report are unlikely to deter them from reducing the benchmark interest rate by 0.25%.

The BLS will publish October’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) report on November 13. Watch for HRE's summary and analysis shortly after its release.