Fiat money is money whose value is derived from a government decree, or fiat. It is not backed by a commodity and the value of the material it is made of is insignificant.

The value of the paper on which a $5 bill is printed is less than $5. The currency, or Federal Reserve Note, is not redeemable in gold, silver, or another asset. (This does not mean it cannot be used to purchase any of these commodities at the market price.) The bill is recognized as legal tender because the government designates it as such, and its value is derived from its acceptance.

The value of fiat money is determined by supply and demand, which are influenced by the stability of an economy and the management of the money supply by the central bank. Printing too much money causes hyperinflation. During hyperinflation, the public is reluctant to accept the currency, resulting in a worthless currency. When the public no longer accepts the value of fiat money, it will turn to commodities such as gold or silver to trade. Unlike representative money, which has an asset backing the currency, fiat does not have the protection of the underlying value of an asset. However, the supply of fiat money is not limited to the supply of an underlying asset, as representative money is, giving policymakers more flexibility in exercising monetary policy.

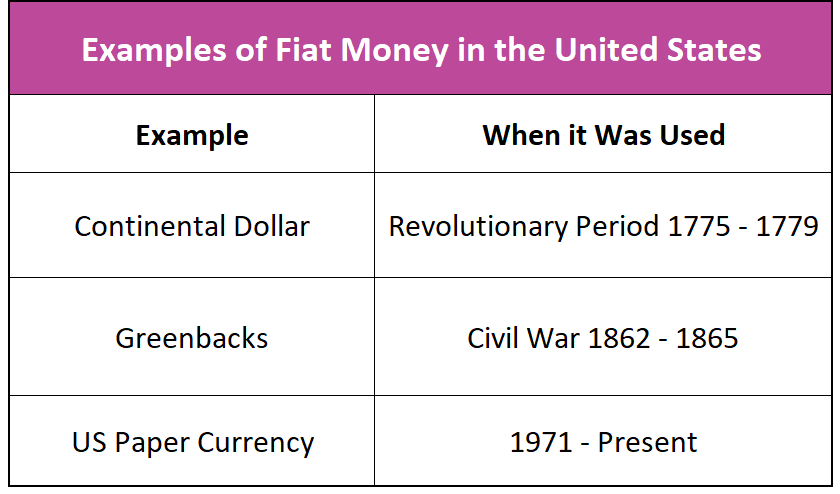

Fiat money became standard in 1971 following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, and President Nixon declared the United States would no longer convert dollars into gold.